Direct Current Sintering and Its Relationship to FAST and Spark Plasma Sintering

Direct current sintering has emerged as an essential technology in advanced materials manufacturing, offering an efficient and highly controlled route to densify metals, ceramics, composites, and nanostructured powders. While the term itself describes a specific approach—using a continuous direct current combined with pressure to consolidate powdered materials—it is best understood within the broader context of Field-Assisted Sintering Technology (FAST). FAST represents an entire class of electrically assisted sintering methods that includes both direct current sintering (DCS) and the more widely recognized Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS). Together, these processes have reshaped what is possible in high-performance material production, reducing cycle times, lowering processing temperatures, and preserving critical microstructural features that conventional furnace sintering cannot maintain.

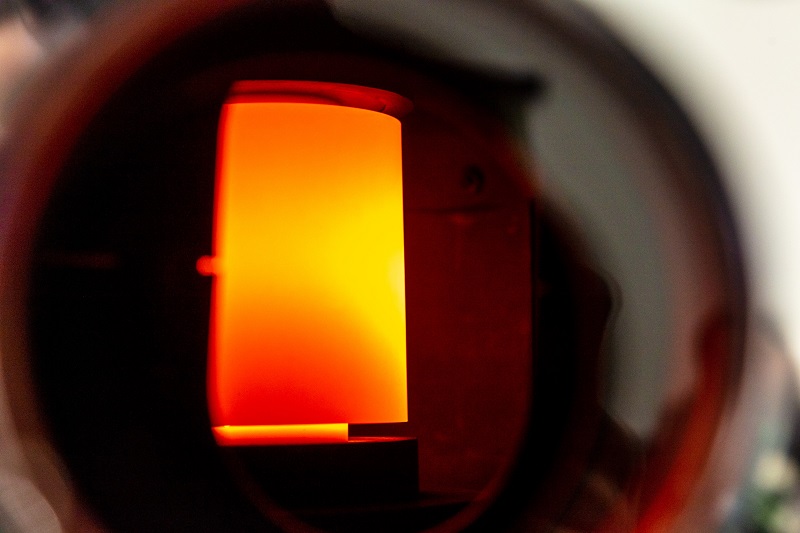

Direct current sintering begins with a deceptively simple concept: by passing a steady direct current through a conductive die—and in many cases through the powder itself—the system generates extremely rapid internal heating through Joule resistance. This differs fundamentally from conventional sintering, in which heat is applied externally, slowly transferred through the furnace walls, and absorbed by the material. In direct current sintering, heat originates within the compact, allowing the material to reach target temperatures much more quickly, often in minutes rather than hours. When combined with uniaxial pressure, this internal heat accelerates particle bonding, surface diffusion, plastic deformation, and neck formation, all of which lead to rapid densification. Because of its efficiency and ability to limit grain growth, DCS is commonly used for refractory metals, metal-matrix composites, and components that benefit from high density without sacrificing microstructural stability.

Spark Plasma Sintering, although closely related, introduces an additional dimension to the process through its use of pulsed direct current. Rather than supplying a continuous electrical signal, SPS repeatedly turns the current on and off in controlled pulses. Historically, this pulsing was believed to produce microscopic sparks or plasma discharges between powder particles—hence the name Spark Plasma Sintering. While subsequent research has shown that true plasma formation is rare, the pulsing itself plays a meaningful role in how heat is distributed and how surfaces interact. Pulsed current can help break down surface oxides, enhance diffusion pathways, and improve uniformity during consolidation. As a result, SPS is particularly valuable for ceramics, thermoelectric materials, nanomaterials, and other advanced systems where fine microstructure control is essential.

Understanding the distinction between direct current sintering and spark plasma sintering requires framing both processes within the broader category of Field-Assisted Sintering Technology. FAST is the umbrella term used to describe any sintering method that combines mechanical pressure with an electrical field to accelerate material densification. Whether that electrical energy is delivered as a steady direct current or as a sequence of controlled pulses, the defining characteristic of FAST is that heat is generated internally through electrical resistance. This internal heating dramatically shortens cycle times and reduces the temperatures necessary for effective consolidation. Under the FAST classification, continuous and pulsed current systems are simply different modes of achieving the same overarching goal: faster, cleaner, more efficient sintering with unparalleled control over temperature, uniformity, and microstructure.

The dramatic advantages of FAST-based sintering over conventional furnace sintering cannot be overstated. Traditional methods rely on slow, external heating that requires far more time and energy to penetrate the material. They also expose components to prolonged high-temperature conditions that inevitably cause grain growth, reducing material strength and performance. FAST methods, by contrast, reduce total time at temperature, meaning grains remain smaller and more uniform. This leads to improved mechanical properties, exceptional hardness, enhanced wear resistance, and higher overall material stability. In addition, the combination of electrical current and pressure allows FAST processes to consolidate materials that are difficult or nearly impossible to sinter using conventional techniques.

One of the leading industrial adopters of FAST technology is California Nanotechnologies, a company known for its specialization in advanced material development. Their production environment makes strategic use of FAST/SPS hybrid systems, enabling them to fabricate nanostructured metals, ceramic composites, and high-performance prototypes with remarkable speed and precision. For companies operating in aerospace, defense, energy, and other high-technology sectors, the ability to rapidly consolidate powders into fully dense, performance-ready components offers a significant competitive advantage. With FAST systems, California Nanotechnologies can produce parts at lower temperatures, maintain nanometer-scale microstructures, and deliver nearly theoretical densities—all while reducing cycle time from hours to minutes.

The importance of this capability becomes especially clear in fields like thermoelectrics, advanced ceramics, and metal-matrix composites, where maintaining microstructural integrity is essential for achieving performance targets. For example, thermoelectric materials rely on finely tuned grain boundaries to optimize electrical and thermal conductivity. Conventional sintering would destroy these delicate structures, but FAST methods preserve them by minimizing exposure to high heat. Similarly, the production of ultra-hard materials or refractory metals benefits from the intense localized heating and applied pressure of FAST systems, enabling densification without melting or degrading the material.

Direct current sintering, as a specific mode within FAST, remains particularly effective for metals and metal-based systems, where steady, uniform heat promotes consistent densification. Its simplicity is part of its strength: by avoiding the complexities of pulsed power systems, DCS provides predictable, repeatable results ideal for certain industrial applications. Spark Plasma Sintering, on the other hand, offers unmatched control for applications that demand microstructural precision. Although both approaches share the same fundamental principles—electrical energy, mechanical pressure, and rapid internal heating—the choice between them often depends on the material, the desired microstructure, and the performance requirements of the final component.

What ties all these approaches together is the underlying recognition that modern materials require modern manufacturing techniques. FAST, in all its variations, unlocks new possibilities by giving engineers unprecedented control over how powders are consolidated. Whether through the continuous energy of direct current sintering or the dynamic pulsing of SPS, these methods represent the future of materials engineering. They reduce energy consumption, shorten production cycles, and preserve microstructural features that were once impossible to maintain during processing. As companies like California Nanotechnologies continue to refine and expand these capabilities, the role of electrically assisted sintering will only grow more important in the creation of next-generation materials.

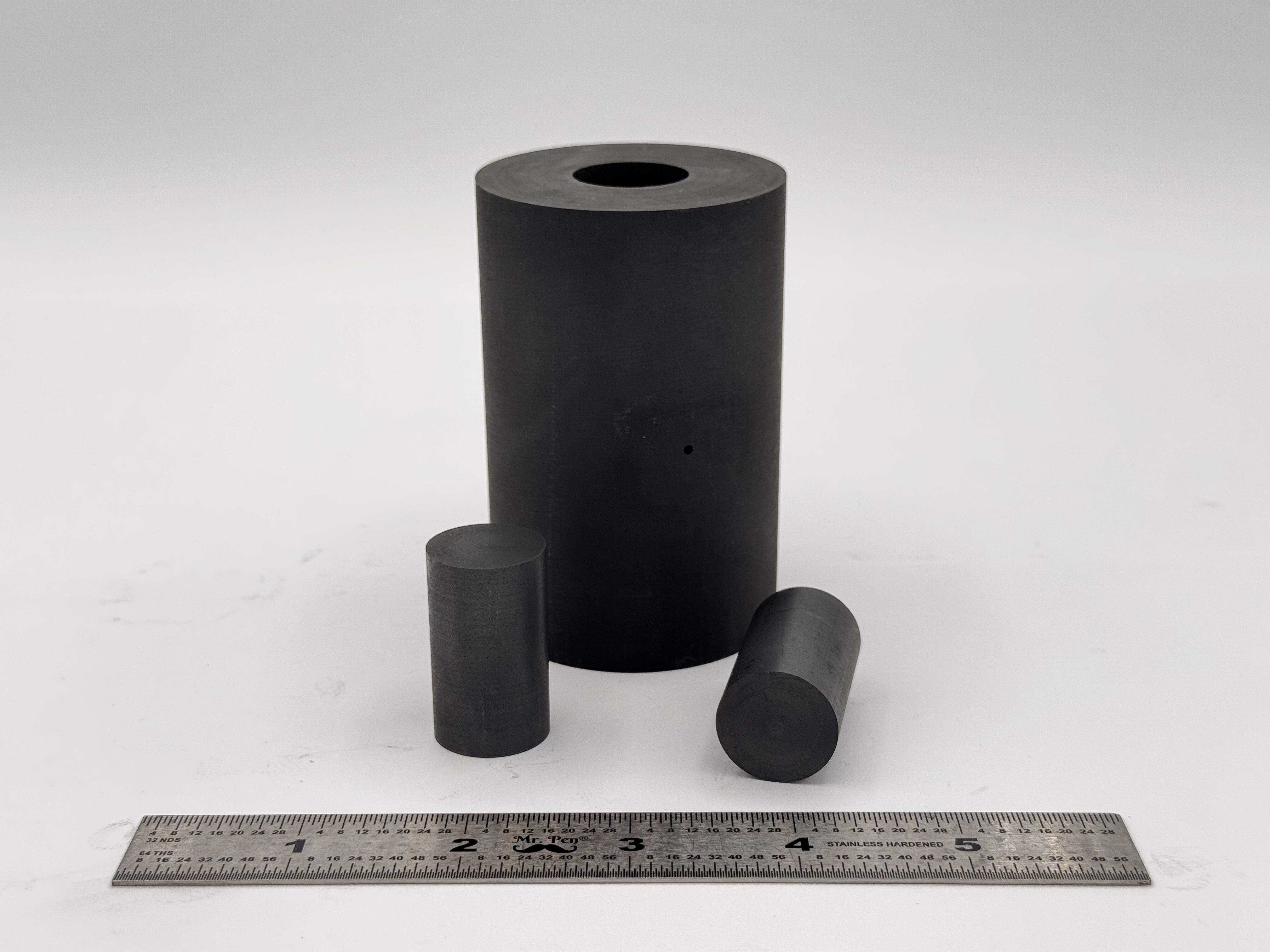

High Strength SPS Graphite Tooling

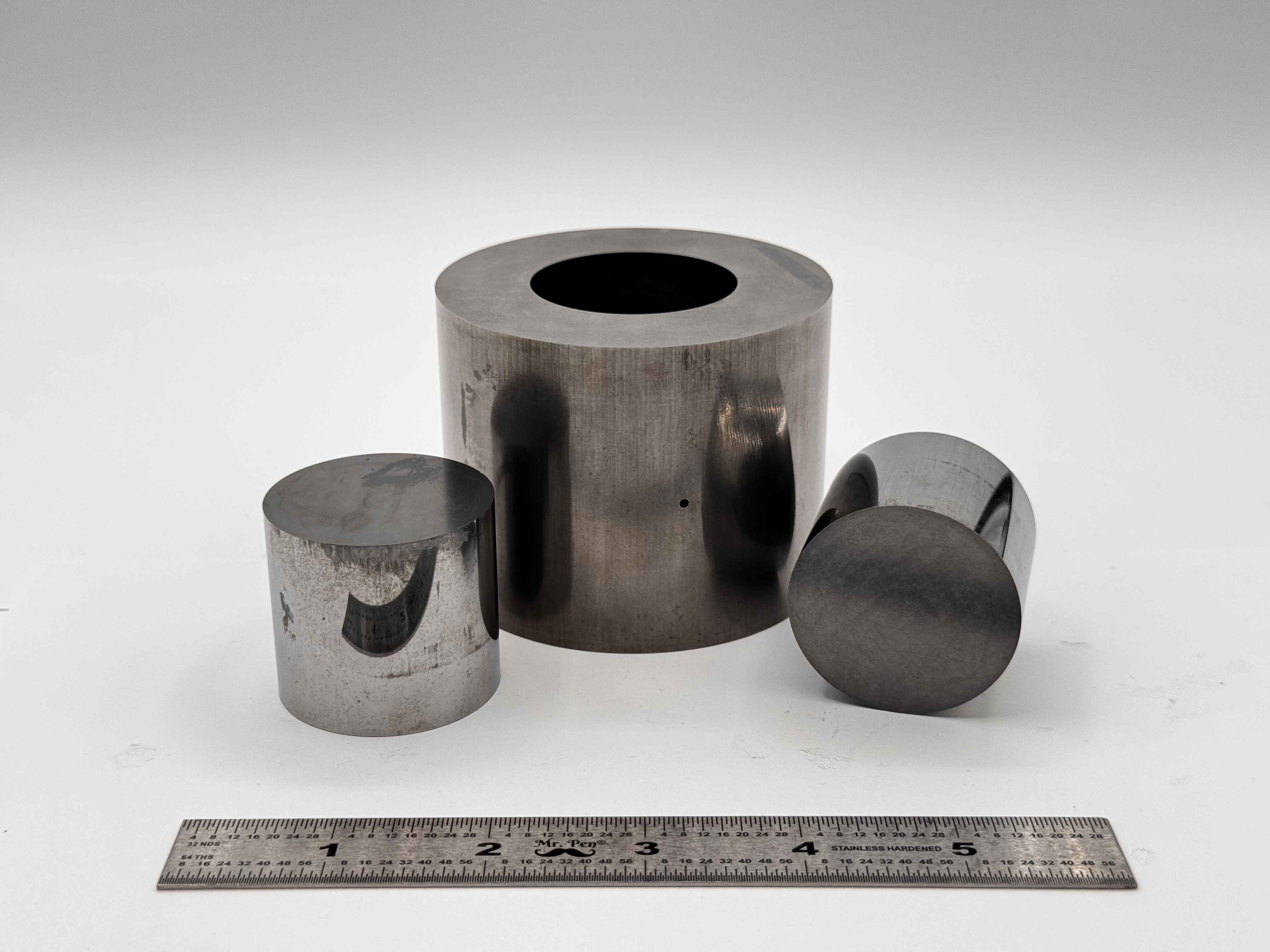

High Strength SPS Graphite Tooling Tungsten Carbide Tooling

Tungsten Carbide Tooling Carbon Graphite Foil / Paper

Carbon Graphite Foil / Paper Carbon Felt and Yarn

Carbon Felt and Yarn Spark Plasma Sintering Systems

Spark Plasma Sintering Systems SPS/FAST Modeling Software

SPS/FAST Modeling Software